THESEUS set out to free the bandit-ridden coast road which led from Troezen to Athens. He would pick no quarrels but take vengeance on all who dared to molest him, making the punishment fit the crime, as was Heracles’s way. At Epidaurus, Periphetes the cripple waylaid attacked him. Periphetes, whom some call Poseidon’s son, and others the son of Hephaestus and Anticleia, owned a huge brazen club, with which he used to kill wayfarers; hence his nickname Corunetes, or ‘cudgel-man’.

Theseus wrenched the club from his hands and battered him to death. Delighted with its size and weight, he proudly carried it about ever afterwards; and though he himself had been able to parry its murderous swing, in his hands it never failed to kill.

b. At the narrowest point of the Isthmus, where both the Corinthian and Saronic Gulfs are visible, lived Sinis, the son of Pemon; or, some say, of Polypemon and Sylea, daughter of Corinthus, who claimed to be Poseidon’s bastard. He had been nicknamed Pityocamptes, or ‘pinebender’, because he was strong enough to bend down the tops of pine-trees until they touched the earth, and would often ask innocent passers-by to help him with this task, but then suddenly release his hold. As the tree sprang upright again, they were hurled high into the air, and killed by the fall. Or he would bend down the tops of two neighbouring trees until they met, and tie one of his victim’s arms to each, so that he was torn asunder when the trees were released.

d. Some, however, say that Theseus killed Sinis many years later, and rededicated the Isthmian Games to him, although they had been founded by Sisyphus in honour of Melicertes, the son of Ino.

e. Next, at Crommyum, he hunted and destroyed a fierce and monstrous wild sow, which had killed so many Crommyonians that they no longer dared plough their fields. This beast, named after the crone who bred it, was said to be the child of Typhon and Echidne.

f. Following the coast road, Theseus came to the precipitous cliffs rushing sheer from the sea, which had become a stronghold of the bandit Sciron; some call him a Corinthian, the son of Pelops, or of Poseidon; others, the son of Henioche and Canethus. Sciron used to seat himself upon a rock and force passing travellers to wash his feet: when they stooped to the task he would kick them over the cliff into the sea, where a giant turtle swam about, waiting to devour them. (Turtles closely resemble tortoises, except that they are larger, and have flippers instead of feet.) Theseus, refusing to wash Sciron’s feet, lifted him from the rock and flung him into the sea.

h. The cliffs of Sciron rise close to the Molurian Rocks, and over them runs Sciron’s footpath, made by him when he commanded the armies of Megara. A violent north-western breeze which blows seaward across these heights is called Sciron by the Athenians.

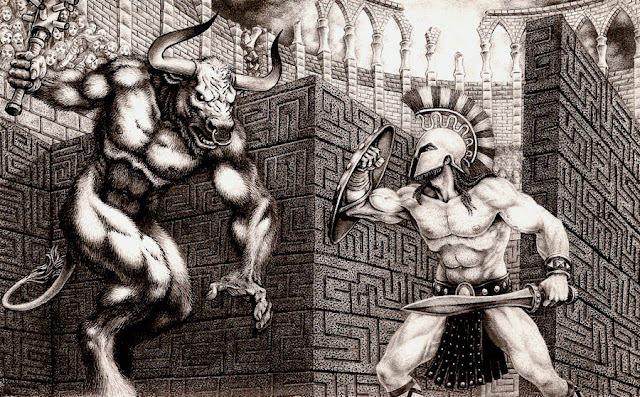

i. Now, sciron means ‘parasol’; and the month of Scirophorionis so called because at the Women’s Festival of Demeter and Core, on the twelfth day of Scirophorionis, the priest of Erechtheus carries a white parasol, and a priestess of Athene Sciras carries another in solemn procession from the Acropolis-for on that occasion the goddess’s image is daubed with sciras, a sort of gypsum, to commemorate the white image which Theseus made of her after he had destroyed the Minotaur.

j. Continuing his journey to Athens, Theseus met Cercyon the Arcadian, whom some call the son of Branchus and the nymph Argiope; others, the son of Hephaestus, or Poseidon. He would challenge passers-by to wrestle with him and then crush them to death in his powerful embrace; but Theseus lifted him up by the knees and, to the delight of Demeter, who witnessed the struggle, dashed him headlong to the ground. Cercyon’s death was instantaneous. Theseus did not trust to strength so much as to skill, for he had invented the art of wrestling, the principles of which were not hitherto understood. The Wrestling-ground of Cercyon is still shown near Eleusis, on the road to Megara, close to the grave of his daughter Alope, whom Theseus is said to have ravished.

k. On reaching Attic Coridallus, Theseus slew Sinis’s father Polypemon, surnamed Procrustes, who lived beside the road and had two beds in his house, one small, the other large. Offering a night’s lodging to travellers, he would lay the short men on the large bed, and rack them out, to fit it; but the tall men on the small bed, sawing off as much of their legs as projected beyond it. Some say, however, that he used only one bed, and lengthened or shortened his lodgers according to its measure. In either case, Theseus served him as he had served others.

2. Since the North Wind, which bent the pines, was held to fertilize women, animals, and plants, ‘Pityocamptes’ is described as the father of Perigune, a cornfield-goddess. Her descendants’ attachment to wild asparagus and rushes suggests that the sacred baskets carried in the Thesmophoria Festival were woven from these, and therefore tabooed for ordinary use. The Crommyonian Sow, alias Phaea, is the white Sow Demeter, whose cult was early suppressed in the Peloponnese. That Theseus went out of his way to kill a mere sow troubled the mythographers: Hyginus and Ovid, indeed, make her a boar, and Plutarch describes her as a woman bandit whose disgusting behaviour earned her the nickname of ‘sow’. But she appears in early Welsh myth as the Old White Sow, Hen Wen, tended by the swineherd magician Coll ap Collfrewr, who introduced wheat and bees into Britain; and Demeter’s swineherd magician Eubuleus was remembered in the Thesmophoria Festival at Eleusis, when live pigs were flung down a chasm in his honour. Their rotting remains later served to fertilize the seed-corn (Scholiast on Lucian’s Dialogues Between Whores).

3. The stories of Sciron and Cercyon are apparently based on a series of icons which illustrated the ceremony of hurling a sacred king as a pharmacos from the White Rock. The first hero who had met his death here was Melicertes, namely Heracles Melkarth of Tyre who seems to have been stripped of his royal trappings-club, lion-skin, and buskins-and then provided with wings, live birds, and a parasol to break his fall . This is to suggest that Sciron, shown making ready to kick a traveller into the sea, is the pharmacos being prepared for his ordeal at the Scirophoria, which was celebrated in the last month of the year, namely at midsummer; and that a second scene, explained as Theseus’s wrestling with Cercyon, shows him being lifted off his feet by his successor (as in the terracotta of the Royal Colonnade at Athens-Pausanias), while the priestess of the goddess looks on delightedly. This is a common mythological situation: Heracles, for instance, wrestled for a kingdom with Antaeus in Libya, and with Eryx in Sicily; Odysseus with Philomeleides on Tenedos. A third scene, taken for Theseus’s revenge on Sciron, shows the pharmacos hurtling through the air, parasol in hand. In a fourth, he has reached the sea, and his parasol is floating on the waves-the supposed turtle, waiting to devour him, was surely the parasol, since there is no record of an Attic turtle cult. The Second Vatican Mythographer makes Daedalus, not Theseus, kill Sciron, probably because of Daedalus’s mythic connection with the pharmacos ritual of the partridge king.

5. Cercyon’s name connects him with the pig cult. So does his parentage: Branchus refers to the grunting of pigs, and Argiope is a synonym for Phaea. It will have been Poseidon’s son Theseus who ravished Alope: that is to say, suppressed the worship of the Megarean Moon- goddess as Vixen.

6. Sinis and Sciron are both described as the hero in whose honour the Isthmian Games were rededicated; Sinis’s nickname was Pityocamptes; and Sciron, like Pityocamptes, was a north-easterly wind. But since the Isthmian Games had originally been founded in memory of Heracles Melkarth, the destruction of Pityocamptes seems to record the suppression of the Boreas cult in Athens-which was, however, revived after the Persian Wars. In that case, the Isthmian Games are analogous to the Pythian Games, founded in memory of Python, who was both the fertilizing North Wind and the ghost of the sacred king killed by his rival Apollo. Moreover, ‘Procrustes’, according to Ovid and the scholiast on Euripides’s Hippolytus, was only another nickname for Sinis-Pityocamptes; and Procrustes seems to be a fictional character, invented to account for a familiar icon: the hair of the old king-Samson, Pterelaus, Nisus, Curoi, Llew Llaw, or whatever he may have been called-is tied to the bedpost by his treacherous bride, while his rival, axe in hand, is preparing to destroy him. ‘Theseus’ and his Hellenes abolished the custom of throwing the old king over the Molurian Rock, and rededicated the Games to Poseidon at Ino’s expense, Ino being one of Athene’s earlier titles.

Comments

Post a Comment