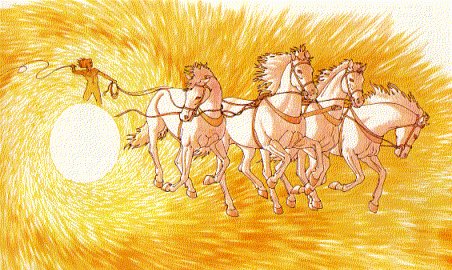

HELIUS, whom the cow-eyed Euryphaessa, or Theia, bore to the Titan Hyperion, is a brother of Selene and Eos. Roused by the crowing of the cock, which is sacred to him, and heralded by Eos, he drives by four-horse chariot daily across the Heavens from a magnificent palace in the far east, near Colchis, to an equally magnificent far-western palace, where his unharnessed horses pasture in the Islands of the Blessed. He sails home along the Ocean stream, which flows around the world, embarking his chariot and team on a golden ferry-boat made for him by Hephaestus, and sleeps all night in a comfortable cabin.

b. Helius can see everything that happens on earth, but is not particularly observant-once he even failed to notice the robbery of his sacred cattle by Odysseus’s companions. He has several herds of such cattle, each consisting of three hundred and fifty head. Those in Sicily are tended by his daughters Phaetusa and Lampetia, but he keeps his finest herd in the Spanish island of Erytheia. Rhodes is his freehold. It happened that, when Zeus was allotting islands and cities to the various gods, he forgot to include Helius among these, and ‘Alas!’ he said, ‘now I shall have to begin all over again.’

‘No, Sire,’ replied Helius politely, ‘today I noticed signs of a new island emerging from the sea, to the south of Asia Minor. I shall be well content with that.’

c. Zeus called the Fate Lachesis to witness that any such new island should belong to Helius; and, when Rhodes had risen well above the waves, Helius claimed it and begot seven sons and a daughter there on the Nymph Rhode. Some say that Rhodes had existed before this time, and was re-emerging from the waves after having been overwhelmed by the great flood which Zeus sent. The Telchines were its aboriginal inhabitants and Poseidon fell in love with one of them, the nymph Halia, on whom he begot Rhode and six sons; which six sons insulted Aphrodite in her passage from Cythera to Paphos, and were struck mad by her; they ravished their mother and committed other outrages so foul that Poseidon sank them underground, and they became the Eastern Demons. But Halia threw herself into the sea and was deified as Leucothea-though the same story is told of Ino, mother of Corinthian Melicertes. The Telchines, foreseeing the flood, sailed away in all directions, especially to Lycia, and abandoned their claims on Rhodes. Rhode was thus left the sole heiress, and her seven sons by Helius ruled in the island after its re-emergence. They became famous astronomers, and had one sister named Electryo, who died a virgin and is now worshipped as a demi-goddess. One of them, by name Actis, was banished for fratricide, and fled to Egypt, where he founded the city of Heliopolis, and fist taught the Egyptians astrology, inspired by his father Helius. The Rhodians have now built the Colossus, seventy cubits high, in his honour. Zeus also added to Helius’s dominions the new island of Sicily, which had been a missile flung in the battle with the Gigants.

d. One morning Helius yielded to his son Phaëthon who had been constantly plaguing him for permission to drive the sun-chariot. Phaëthon wished to show his sisters Prote and Clymene what a free fellow he was: and his fond mother Rhode (whose name is uncertain because she had been called by both her daughters’ names and by that of Rhode) encouraged him. But, not being strong enough to check the career of the white horses, which his sisters had yoked for him, Phaëthon drove them first so high above the earth that everyone shivered, and then so near the earth that he scorched the fields. Zeus, in a fit of rage, killed him with a thunderbolt, and he fell into the river Po. His grieving sisters were changed into poplar-trees on its banks, which weep amber tears; or, some say, into alder-trees.

***

1. The Sun’s subordination to the Moon, until Apollo usurped Helius’s place and made an intellectual deity of him, is a remarkable feature of early Greek myth. Helius was not even an Olympian, but a mere Titan’s son; and, although Zeus later borrowed certain solar characteristics from the Hittite and Corinthian god Tesup and other oriental sun-gods, these were unimportant compared with his command of thunder and lightning. The number of cattle in Helius’s herds-the Odyssey makes him Hyperion-is a reminder of his tutelage to the Great Goddess: being the number of days covered by twelve complete lunations, as in the Numan year (Censorinus), less the five days sacred to Osiris, Isis, Set, Horus, and Nephthys. It is also a multiple of the Moon-numbers fifty and seven. Helius’s so-called daughters are, in fact, Moon-priestesses-cattle being lunar rather than solar animals in early European myth; and Helius’s mother, the cow-eyed Euryphaessa, is the Moon-goddess herself. The allegory of a sun-chariot coursing across the sky is Hellenic in character; but Nilsson in his Primitive Time Reckoning (1920) has shown that the ancestral clan cults even of Classical Greece were regulated by the moon alone, as was the agricultural economy of Hesiod’s Boeotia. A gold ring from Tiryns and another from the Acropolis at Mycenae prove that the goddess controlled both the moon and the sun, which are placed above her head.

2. In the story of Phaëthon, which is another name for Helius himself (Homer: Iliad and Odyssey), an instructive fable has been grafted on the chariot allegory, the moral being that fathers should not spoil their sons by listening to female advice. This fable, however, is not quite so simple as it seems: it has a mythic importance in its reference to the annual sacrifice of a royal prince, on the one day reckoned as belonging to the terrestrial, but not to the sidereal year, namely that which followed the shortest day. The sacred king pretended to die at sunset; the boy interrex was at once invested with his titles, dignities, and sacred implements, married to the queen, and killed twenty-four hours later: in Thrace, torn to pieces by women disguised as horses, but at Corinth, and elsewhere, dragged at the tail of a sun- chariot drawn by maddened horses, until he was crushed to death. Thereupon the old king reappeared from the tomb where he had been hiding, as the boy’s successor. The myths of Glaucus, Pelops, and Hippolytus (‘stampede of horses’), refer to this custom, which seems to have been taken to Babylon by the Hittites.

3. Black poplars were sacred to Hecate, but the white gave promise of resurrection; thus the transformation of Phaëthon’s sisters into poplars points to a sepulchral island where a college of priestesses officiated at the oracle of a tribal king. That they were also said to have been turned into alders supports this view: since alders fringed Circe’s Aeaea (‘wailing’), a sepulchral island lying at the head of the Adriatic, not far from the mouth of the Po (Homer: Odyssey). Alders were sacred to Phoroneus, the oracular hero and inventor of fire. The Po valley was the southern terminus of the Bronze Age route down which amber, sacred to the Sun, travelled to the Mediterranean from the Baltic.

4. Rhodes was the property of the Moon-goddess Danaë-called Cameira, Ialysa, and Linda-until she was extruded by the Hittite Sun-god Tesup, worshipped as a bull. Danaë may be identified with Halia (‘of the sea’), Leucothea (‘white goddess’), and Electryo (‘amber’). Poseidon’s six sons and one daughter, and Helius’s seven sons, point to a seven- day week ruled by planetary powers, or Titans. Actis did not found Heliopolis-Onn, or Aunis-one of the most ancient cities in Egypt; and the claim that he taught the Egyptians astrology is ridiculous. But after the Trojan War the Rhodians were for a while the only sea- traders recognized by the Pharaohs, and seem to have had ancient religious ties with Heliopolis, the centre of the Ra cult. The ‘Heliopolitan Zeus’, who bears busts of the seven planetary powers on his body sheath, may be of Rhodian inspiration; little similar statues found at Tortosa in Spain, and Byblos in Phoenicia.

Comments

Post a Comment